How Colombia plans to keep its oil and coal in the ground

J Torres/ Getty Images

J Torres/ Getty ImagesThe country’s new president has been vocal about plans to leave fossil fuel extraction behind. But the country faces an uphill struggle to do this in practice.

In February 2020, the lifeblood that kept the tiny town of La Jagua de Ibirico in northern Colombia going stopped flowing.

As the Covid-19 pandemic sunk coal prices internationally, the multinational giant Glencore, through its local Prodeco, closed the two coal mines in the area.

Since the closure, the sky has cleared up and the air is fresher, says Álvaro Castro, a social leader and local researcher for Universidad del Magdalena, who lives in the town. Birds now chirp in the newly green treetops, and the blanket of coal ash covering the rooftops is gone, he says.

But at street level, the situation is dire.

As 7,000 workers – from a workforce of 7,300 – lost their jobs and contractors left town, nearly 100 restaurants, cafes, hotels and other businesses closed, the local branch of the country’s largest coal workers union says. As a result, according to the town's mayor, the municipality lost 85% of its income.

Union leader José Ladeut, one of the few still working at Prodeco’s railroad, says this sudden closure of coal mines in La Jagua de Ibirico should be a cautionary tale for newly elected president, Gustavo Petro. "We were the guinea pigs," he says. "And we weren't ready. The transition found us still wearing nappies."

Petro, an economist and former guerilla who was elected as Colombia's first ever left-wing president in June 2022, rose to power with a socially progressive, environmentally conscious agenda which included a strong message on the need for the country to leave fossil fuels behind.

He promised the nation "a green, not a black future", and told La Jagua de Ibirico and other towns in the coal corridor they would be an essential part of Colombia's transition into a future where coal, oil and gas remain underground. In a speech at the COP27 climate talks in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in early November, Petro said the world needs an "immediate withdrawal from the oil and gas industry".

G Legaria/Getty Images

G Legaria/Getty ImagesDespite the rising momentum around climate action in recent years, the idea of cutting off fossil fuel supply is rarely made much of by world leaders, even at climate conferences. But there is a rising recognition that it is a crucial part of climate action – even the relatively conservative International Energy Agency (IEA) has said there must be no new investment in new gas, oil or coal extraction projects from now on if the world is to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

A recent report from the Tyndall Centre at the University of Manchester found rich countries need to phase out all oil and gas production by 2034, and poorer countries by 2050, to stay on track with the 1.5C target.

Towards Net Zero

Since g the Paris Agreement, how are countries performing on their climate pledges? Towards Net Zero analyses countries' progress and major climate challenges, and their lessons for the rest of the world in cutting emissions.

So far, Colombia is the largest, most fossil-fuel-dependent country adhering to an agenda that explicitly calls to leave fossil fuel extraction behind. "There's really very few countries in the world that have said anything regarding this 'leave it on the ground' idea," says Paola Yanguas-Parra, policy and energy transition economist at the Technical University of Berlin's FossilExit Group.

Last year, Costa Rica and Denmark formed an international alliance to phase out production of fossil fuels, called the Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance (although under its new presidency, Costa Rica has recently backed away from the alliance leadership). Meanwhile, the South Pacific island nation of Tuvalu recently became the second country to call for a Fossil Fuel Non Proliferation Treaty, ing Vanuatu in backing the idea of creating a legal pathway to regulate and phase out the global production of coal, oil and gas. On the coal front, since its launch in 2017, the Powering Past Coal Alliance, has gathered almost 100 countries and subnational governments working to phase out existing unabated coal power generation.

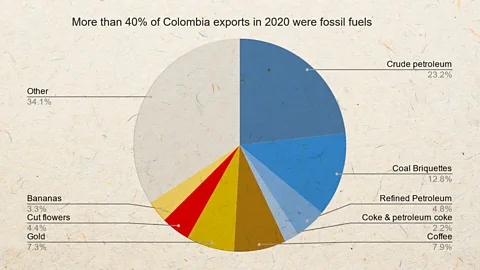

In these cases, however, most official don't heavily depend on fossil fuel extraction, says Yanguas-Parra. Conversely, Colombia is among the top coal producers globally and heavily dependent economically on fossil fuels: between 40 and 50% of its exports are coal and oil. Taxes from the sector and dividends from the partially state-owned oil Ecopetrol – the largest company in the country – for about 9% of the central government's income.

Compared to countries with a similar dependency, "Colombia's goals could be considered very progressive", says Yanguas-Parra. But a transition away from fossil fuels in Colombia will require several major transformations. And economists and energy policy experts agree that, despite the lofty speeches, Colombia is currently far from ready to "keep it in the ground".

Like most nations, to move to a clean economy, the country needs to clean up its energy grid by switching to renewables and electrify industry, homes and transport. But at the same time, Colombia will also need to replace half of its exports and restructure public finances on a national and a regional scale. To make sure the transition is just, it will also need to ensure about 109,000 workers can find new jobs, and that indigenous and black communities living in critical areas for renewable energy development are fairly included and compensated.

You might also like:

Some transformations, like a 100% renewable electric grid, are achievable as soon as 2030, researchers have found. However, other goals, particularly those referring to substituting Colombia's exports, ensuring economic transformation in fossil-dependent regions, and clean-up plans for closing mines and oil fields, are nowhere close to being a reality.

Until Petro's election this year, replacing oil and gas was not part of the energy transition conversation within the government. Colombia has been slowly building its clean energy policy since 2014, when Congress ed a law to promote the building of renewable energy projects – mainly solar and wind power – via tax breaks and other incentives. But in 2021, less than 1% of energy in the country came from these sources.

The former president Iván Duque ed important legislation regulating the renewables market, promoting electric vehicles (EVs) and deg a general energy transition policy. But he also promoted fracking, held auctions for new oil, gas and coal projects, and ed the fossil fuel industry as a "cornerstone" to get out of the economic crisis the pandemic created.

BBC. Source: OEC

BBC. Source: OECYanguas-Parra says failing to recognise Colombia's financial dependency on fossil fuels in clean energy policies has been a mistake. As importing countries decarbonise their own economies, demand could plummet, leaving places like La Jagua de Ibirico extremely vulnerable to abrupt economic recession. This is particularly true in coal towns, as Colombia exports 90% of the coal it extracts.

"What we've seen historically is that when transitions are not planned, the social, economic and cultural repercussions remain for years, and even decades," she says. "It's extremely traumatic." (Read about How a just transition can make India's coal history)

That's exactly what could happen in La Jagua, where the prospects for a just transition currently look bleak.

Here, over the past few decades, taxes and royalties paid by the mining companies have outgrown those of other sectors. The four main coal towns of Cesar – Agustín Codazzi, La Jagua de Ibirico, Becerril and El Paso – represent 35% of the area's entire GDP and 30% of its income. These extraordinary revenues for municipalities have stalled mayors’ willingness to explore other income avenues, leaving many people behind: more than half still live in poverty in Cesar. As the mines pollute air and water, agriculture was lost, even for self-consumption, Álvaro Castro says.

In a way, a similar phenomenon has happened on a national scale. "Colombia has had an artificially strong currency because our exports are commodities paid in dollars," says Juan José Guzmán Ayala, an economist at Columbia's Center on Global Energy Policy. "But those commodities end up flattening the country's industrial growth." Leaving fossil fuels in the ground means finding alternatives incomes to replace them.

Reuters/Nathalia Angarita/Alamy

Reuters/Nathalia Angarita/AlamyThe government's campaign plan proposed to create an Energy Transition Fund with taxes and royalties from the industry to finance the phaseout and promote new economic sectors like agriculture, agroecology and clean energy technologies. However, it's still unclear if the fund will happen, how much money it will receive, and how it will decide where the money should go. It is also unclear what kind of product – or combination of them – has the greatest potential to replace such a big chunk of the country's exports.

A coalition of more than 30 national and international organisations addressed how a transition could be funded in a proposal published earlier this year. New taxes could be placed on the oil and coal industry, it said, (this seems likely, as they are included in a tax reform on the verge of being ed in Congress), while tax exemptions and benefits, which ed for a lost $1.34bn (£1.14bn) in 2020 according to the proposal, could be removed.

A fund like this might help, but it leaves unanswered the question of what mine closures should look like, says Andrea Cardoso, an economist at University of Magdalena in Santa Marta, Colombia. The country's legal framework is largely silent on what happens to workers if a company voluntarily gives up its mining permits: they are legally responsible for the environmental clean-up, but the layoff of workers or responsibility for health outcomes after decades of pollution is hardly mentioned in laws and policies. The lack of clear regulations, Cardoso says, allowed Glencore to close its Prodeco mines with virtually no explanation.

The dismissals came with no notice, and while they included "voluntary retreat" programmes which gave some workers a year's salary and health insurance, the company did not them in finding a new job or repurposing their skills, union say. "With us, the workers and the communities, everything that should not be done in a just transition is being done," Robinson Moreno, a union leader at the country's largest coal workers union, Sintracarbón, says.

A spokesperson for Prodeco rejects the claim that workers were given no , saying workers have been offered counselling and professional programmes "aimed at identifying the occupational life project that best suits their needs, through either an entrepreneurship or a new labour opportunity". The spokesperson says since operations were first suspended "different communication channels have been established with all employees in order to keep them informed about the company's situation and the need to adjust our personnel due to the definitive termination of operations at Calenturitas and La Jagua mines". They add that "the decision to relinquish the mining contracts was not taken lightly and represents a disappointing outcome for the Prodeco Group".

Since the closures, according to the National Mining Agency the company has complied with only about 42% of its environmental obligations. The Prodeco spokesperson says the firm is working with Colombia's National Environmental Licensing Agency to fulfil its environmental obligations, and is awaiting the agency's approval of its proposals.

For Cardoso, many questions remain. "There is a lot of talk about alternatives, ecotourism or agriculture," says Cardoso. "But the communities themselves ask, 'But how can we do that if the soil is contaminated, the air is polluted, the water resources are scarce">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });