An ingenious way to hide a map

Georgina Kenyon

Georgina KenyonIn World War II, clandestine maps were printed onto cloth handkerchiefs to be used by Allied servicemen in case of capture behind enemy lines.

Treasuring my father-in-law’s old cloth hankies sounds unpleasant. But they hold a secret. They are war-time maps that look like handkerchiefs, depicting old boundaries and conflicts in Europe.

Blowing your nose in them was a definite no-no, as it could mean covering up an important escape route: a mountain , a road, an airfield. Your life could depend on these maps.

Also referred to by historians as ‘escape and evasion maps’, handkerchief maps were used in World War II by the Allied forces, such as by my now 94-year-old father-in-law, Howard Walker, who from the age of 20 flew for the Australian Air Force over Italy and the former Yugoslavia. From 1941 to 1945, they were folded in his jacket pocket. Other men hid them in the lining of their coats or boots. Now three of Howard’s handkerchiefs hang behind glass on our living room wall, a reminder of the war.

“In case we were parachuted out or crashed over enemy lines, the hankies gave us some kind of reassurance we would get back to safety,” he told me.

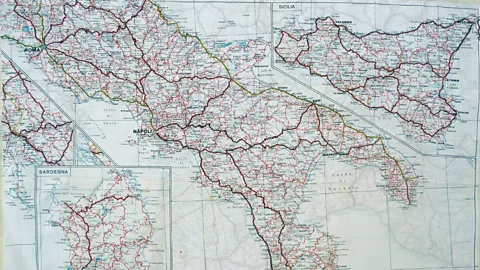

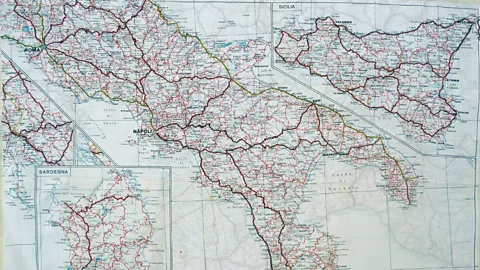

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsHoward’s maps are double-sided with a different map on each. One shows Hungary, Romania and Italy. Another, the Aegean Sea with Greece, Turkey and the Cyclades, with towns, rivers and mountains. On its other side is the ‘boot’ of Italy, depicting Rome, Sicily, Sardinia and Naples. A third portrays Yugoslavia, with northern Italy on the back. Their topographic detail reveals roads and borders.

Roughly half a metre squared, they’re made of silk – easy to fold, able to survive wear and tear and noiseless when unfolded. Early in the war the maps were sometimes printed on paper made from mulberry leaves, which was more durable than paper. When silk became a valuable commodity in the mid-1940s, synthetic fabric such as rayon and acetate was used instead.

Howard’s main role was to drop supplies of guns, explosives, food and clothing to groups of partisans in Yugoslavia, Italy and Greece to delay the return of the retreating Germans who were fighting the Russians. During flight, Howard’s crew were shot at frequently, and he still re the frightening night missions.

“You’d feel the jolt of the supersonic air blast, then the thumping explosion, then see the dirty, greasy-looking puff of dark smoke. Being off course over enemy territory, not knowing where you were was nerve-wracking, particularly at night,” Howard said.

“Europe is very different now, different borders and alliances. But whenever I see the handkerchiefs, I all that international stupidity of the war, all the deaths,” he added, explaining that in many ways, the international crises back then have just led on to others.

“In some ways the war never ended,” he said.

I was reminded of Howard’s words a few years later when I travelled to a very different Italy – to the one depicted in the handkerchiefs.

Georgina Kenyon

Georgina KenyonAs I wandered through the narrow streets of old Naples, I ed locals heading to the nearby market and a handful of tourists wandering the streets. I could still see evidence that the city was one of the most bombed in Europe in World War II, with visible damage to some of the buildings. I made my way past antique and rare bookshops, apartment blocks and down Via dei Tribunale. On the side of the road were ‘Anima Sola’, Roman Catholic wooden figures of ‘lonely souls’ in purgatory. They were housed in glassed-fronted cases, the size of shoe boxes, with red and orange burning flames painted at their feet. The flames licked the doll-sized people while they cowered in fright. The carvings made me think of the war when my father-in-law was in this country, when the world was literally in flames and people did not know their future.

I came to a Baroque Catholic church, Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco, also referred to as the ‘Purgatory Church’ as it was designed for people to pray for those they thought were in purgatory. Inside, I felt goose bumps as I sat in the late-afternoon shadows, the cool stone around me. Like the Anima Sola, the church was doing its best to disturb and warn the er-by of the terrors of this limbo state.

Sculptures of skulls stared down eyeless at me, and paintings and reliefs of skeletons with wings flew above. Such reminders of purgatory suggested being trapped between the ‘old’ world and the ‘new’, and I thought of how it must have felt during the war, not knowing whether you were going to live or die.

I thought of Howard and his crew embarking on their war-time night missions over this country and the trepidation they must have felt. To me, this ‘purgatory’ church, full of its fearful decorations, sculptures and paintings, also represented the very human need to be reassured, that there is a better life ahead; a chance to escape the suffering.

REDA &CO srl/Alamy

REDA &CO srl/AlamyFor Allied aircrews during the war, reassurance of survival was given not only in the handkerchief maps, but also in the form of a ‘survival kit’. According to Howard, these included a packet of high-energy glucose cubes, water-purifying tablets, a comb, a fishing line and hook, a pocket knife with a can opener, a needle and thread and a razor. The latter was important in case it was unfashionable in the country you were lost in to have a beard. You didn’t want to stand out.

Also included was a pair of dry socks; important if you needed to do a lot of walking after you were shot down. Perhaps most importantly, though, were the buttons, covered in phosphorescent dots on one side to show which way was north. These ‘buttons’ worked by having a magnet inside them and could be sewn into the aircrew’s clothes.

According to Howard, these kits and maps were just as important psychologically as they were practical. Although all his crew survived the war and did not have to use the handkerchief maps, they were kits of hope: They prepared people in ‘escape-mindedness’ – they readied you for the worst while steadying your nerves.

Laura Di Biase/Alamy

Laura Di Biase/AlamyOn a visit to see Howard back in Melbourne, he told me a few more lessons he’d learned from the war, of how not to lose your way.

“Keep your sense of humour, and have an escape kit with you at all times.”

But most of all, he reminded me, that individuals are more important than politics or ideologies. World leaders may still debate who their enemies and allies are, or where capitals and boundaries should lie, but maps of these borders between countries soon become redundant and disposable, scrunched up like a handkerchief.

Travel Journeys is a BBC Travel series exploring travellers’ inner journeys of transformation and growth as they experience the world.

more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.